Human Error and How History Repeats Itself

In an industry where the need for accuracy and compliance is essential, there is a category of error which still occurs at an astounding rate, affecting both cost and product availability. In the case where the human is part of the process, there will always be a “human error” factor. This is the largest variable in the manufacturing process. The interesting part is that most of the errors are preventable, especially given that the most common area where the FDA finds observations is related to procedures.

Why is it that writing and following procedures is one of the most cited issues by the FDA? Procedures have been required since the beginning of time, or as part of every pharmaceutical and biotech facility in my career. Companies struggle to write good procedures. The evidence is clear… this is an easy win to eliminate many regulatory findings. As shown below, history continues to repeat itself with regards to procedures.

| Year | Drug Observations | Device Observations |

| 2020 | 382 of 1513 | 987 of 1602 |

| 2015 | 897 of 3626 | 2215 of 4083 |

| 2010 | 1043 or 3796 | 1457 or 4132 |

| 2006 | 938 of 3503 | 1376 of 4444 |

Inspection Observations (24 November, 2020)

In the development and implementation of procedures, there are common issues, listed below, which have repeated themselves throughout the history of this industry. Consistently for over 20 years, these are the top findings – not just top procedure findings, but top overall findings for both drugs and devices. They include:

- Procedures not in writing, fully followed

- Lack of or inadequate procedures

- Lack of or inadequate complaint procedures

If we know there are repeat findings over the history of the industry, why can’t we fix the problem? Several companies believe they write “good procedures”. Let’s look at what some call good procedures. Examples include:

- Over 100 pages long

- Information included not relevant to the operation

- Double digit revisions in a short period of time (2-3 years)

- No hands-on training for procedures required to operate and maintain equipment

These examples create an environment inviting operators and technicians to take shortcuts or create “unapproved” procedures leading to deviations, CAPAs, and in some cases batches of drug product which are either quarantined or must be destroyed. If you were an operator on the floor pushed to make deadlines, could you find the steps you need to perform in a 100 page procedure? It might be a little challenging.

In today’s industry there are several types of documents within the category of procedures. These include “policies”, “standard operating procedures (SOPs)”, work instructions, and job aids. For the sake of this discussion, we will focus on the SOP, which has become everything except standard. These have been the core documents of pharmaceutical and biotechnology operations for many years, and there have been many variations in the approach for these documents, mostly because organizations fail to establish good standards for those who are asked to write them.

So, what should an SOP consist of? First and foremost, it should be concise and easy to follow. The word “standard” should indicate this will be the way we operate and maintain our equipment. Major parts of the document should include

- Purpose – What purpose does the SOP serve? Why are you writing this document?

- Scope – Most equipment or systems are large, cover large processes, and/or require different major tasks such as operations and maintenance. Be specific in this section to address the scope of the system or process that the SOP covers.

- Tasks – Be specific and start each step with an action verb. Be concise and write the important information first. Don’t leave the reader a pool of information to wade through before getting to the action required. This is after all a “standard operating procedure”.

- Supporting information – Use tables and drawings only as necessary to support the tasks required in the SOP.

One obvious mistake organizations often make when writing the SOP is not involving others – specifically, the users of the document and experts on the processes. Seeing the document through the eyes of the users can lead to some important information being included. After all, if they can’t follow it, then what good is the SOP? They can just make up their own steps… which, by the way, can lead to another preventable audit finding or lost batch.

So now what don’t we include? Anything that is not specific to the task being performed. The SOP is not a training document, it is a procedure. While it certainly is part of the training process, the SOP is not THE training document. Every operator needs to understand why and how things work. The SOP is not the place for that knowledge transfer to take place. The SOP should be scannable and easy to read. An SOP is “…a set of instructions that describes all the relevant steps and activities of a process or procedure. (https://www.process.st/writing-standard-operating-procedures/).

Why does history repeat itself when it comes to writing procedures that lead to the same findings in audits are repeated year after year? It is as simple as this…in my experience, SOPs don’t get the attention they require. They are often left until the last minute and rushed to be created by an unqualified author.

In this Blog, I have outlined some simple parts of an SOP for organizations to use. There is obviously much more to consider on the technical writing side of this effort, but following the outline and recommendations above, as well as planning adequate time to write the documents with all the right people can prevent history from repeating itself in your organization. These documents are in the hands of our front-line supervisors, technicians and operators every day. Therefore, SOPs need to be made effective and useful for these people to easily follow.

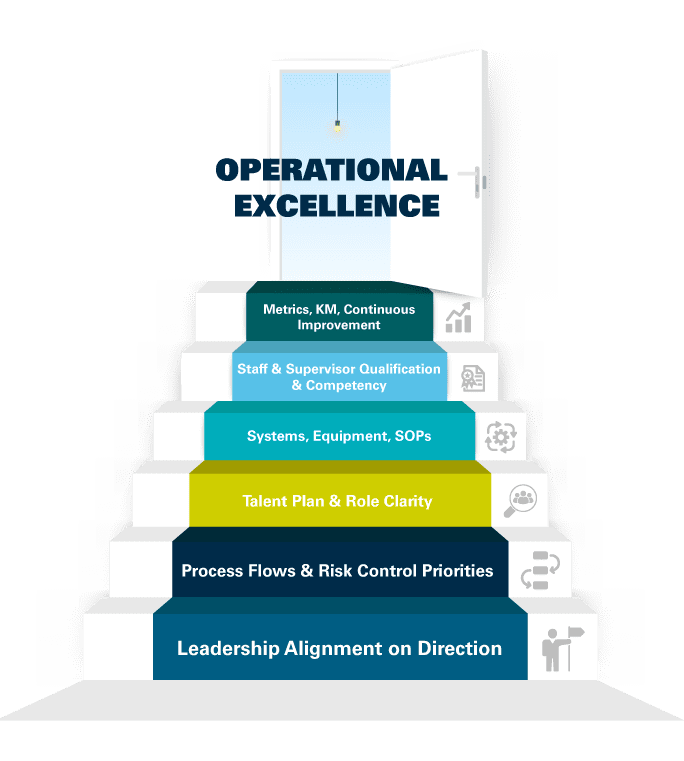

Follow CAI’s Human Performance articles as we highlight the practical approach to each step of our modeled path toward operational excellence:

References:

About the Author

Jeff Hall – Human Performance Consultant

Jeff Hall – Human Performance Consultant

Jeff Hall is an Associate Director in Human Performance services with over 30 years of experience with implementing programs to support the start-up, operation, and maintenance of process systems and equipment. He has over 20 years of experience managing projects of up to $6M and leading groups of people ranging from one to over 25 persons. Jeff has an MBA and is an expert in Project Management. He uses the skills in these two areas to manage project costs and efficiency. He has used this approach to create focused, effective, and efficient organizations and successful project implementation. He is experienced in auditing, developing programs, and leading projects in GMP, GLP, and GCP environments.